City Ditch is the oldest historic structure in Littleton. It has Water Right Number 1 on the South Platte River. After gold was discovered in this region in 1859, gold seekers were soon swelling the little settlement near the South Platte River that would become Denver. The need for water for the residents of this settlement was increasing. The Capitol Hydraulic Company was formed in late 1859 for the purpose of building a ditch to bring water into Denver. Construction of the ditch began in 1860. However, engineering and financial issues caused the abandonment of the project by summer of 1861.

After financing for the ditch project became available again, the Capitol Hydraulic Company reorganized in 1864. The company hired Richard Little, a New Hampshire surveyor who made his way to Denver. Richard Little had staked a claim to the land where work on the original Ditch had been started.

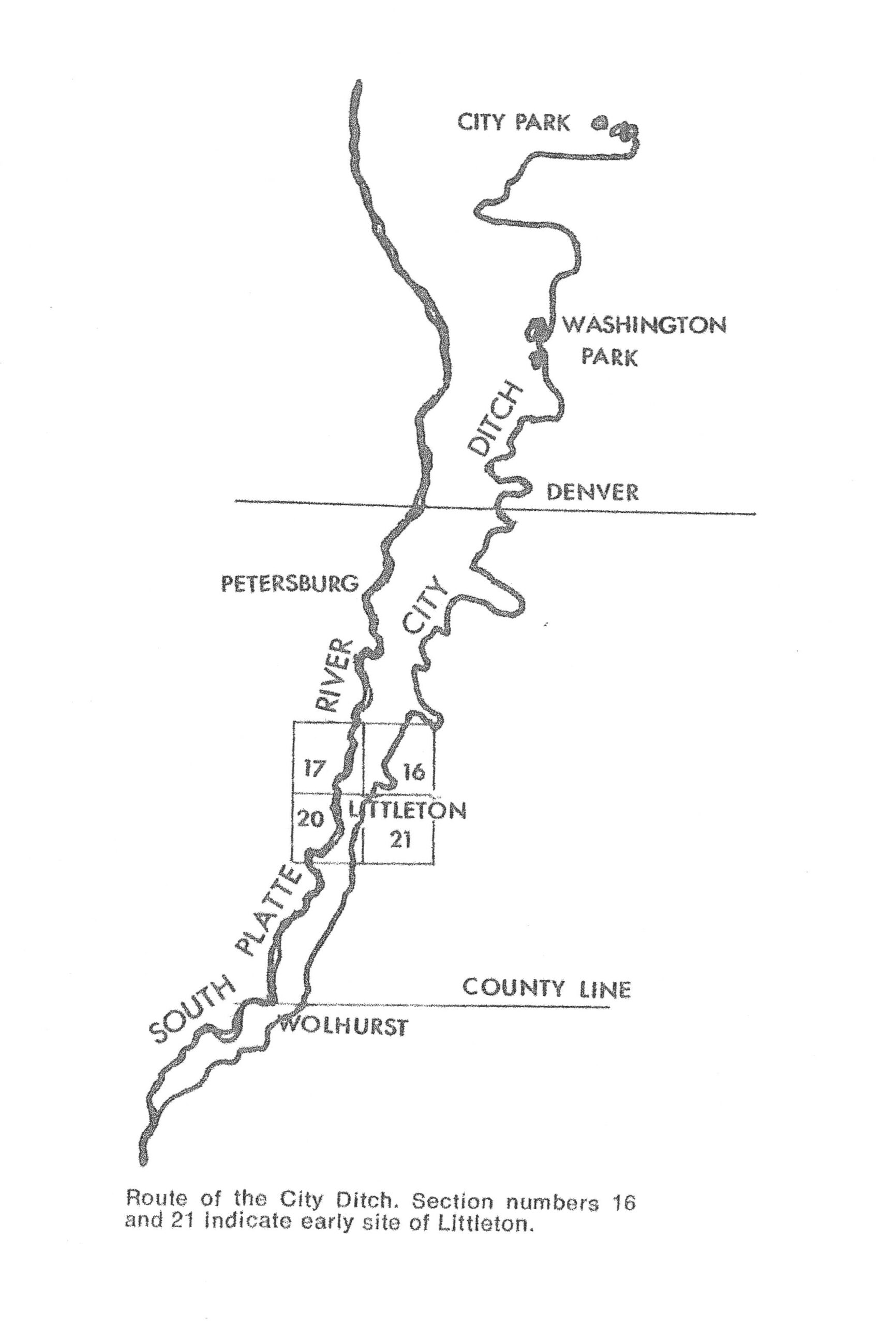

As a surveyor, he had explained to the Capitol Hydraulic Company that the diversion point needed to be moved further south and upstream to the junction of the South Platte and Plum Creek. He agreed to provide a new route survey and be the general manager of the construction effort. The new diversion from the South Platte River was relocated 4 miles upstream from the earlier diversion point at a location that is under what is now under Chatfield Reservoir. Work commenced on the new ditch plan in the fall of 1864.

Several years later, in 1867, Richard Little used part of the original ditch alignment that he found suitable for operating a water-powered flour mill and established the Rough and Ready Mill which boosted the economy of the area. City Ditch had provided much needed irrigation water which helped establish the area as an agricultural region. The agricultural growth spurred Richard Little to create the townsite of Littleton in 1872.

John Wesley Smith, a pioneer businessman who would go on to be a successful

Denver miller, banker and railroad executive, contracted with the reorganized company to dig the ditch. Smith’s contract, approved by the Board of Directors of the Capitol Hydraulic Company, on June 23,1864, read in part, “…said Smith to construct a canal or ditch commencing at or near the mouth of Plum Creek below the Platte Canyon … on the East side of said Platte,….. said ditch to have a fall of at least four (4) feet to the mile,… said ditch to be finished at least six (6) feet wide in the bottom and embankments sufficient to carry at least two (2) feet of water, to be constructed so as to receive water out of the Platte River at the point of commencement at or near the mouth of Plum Creek,… to convey the water of said ditch over Cherry Creek at a point to be selected by said Smith in a flume same width at least of the bottom as the canal or ditch.”

Smith’s remuneration was to be half the shares of the Capitol Hydraulic Company stock and $10,000. Instead of hiring men to dig the ditch in the usual way, Smith hired freight wagons to ship two huge, disassembled machines called “Rotary Canal Builder” or “Railroad Excavator” to do the heavy work. When reassembled on the prairie they must have been a sight no one could imagine.

The Rocky Mountain News of December 7, 1864 described the rotary canal builder at the time as,

“A mammoth four wheeled outfit, partaking partly of the appearance of a fire engine, an artillery wagon, a mowing machine and a colossal steam plow…This machine has two mammoth hind wheels and two miniature front ones with a lot of frame and iron mechanism between… that …When worked by eight or ten yoke of cattle, it will do the work of a hundred men per day.”

Imagine how the open prairie landscape looked to those machine operators: no trees (just prairie grass), no railroads (those came six years later), no barbed wire fences (barbed wire came into widespread use ten years later), no improved roads (the first paved “intercity” road was not constructed in Colorado until the next century). For three years, the machines dug their way north across the prairie toward Denver.

Because J.W. Smith owned half the company and was in charge of the digging, as the work progressed, the ditch took on the name, “Smith’s Ditch.” Observing that it would pass near a natural depression, sometimes referred to as a ‘buffalo wallow’ southeast of Denver, Smith routed the ditch in such a way that the depression could be filled with water from the ditch. Smith, ever the astute businessman, saw the opportunity to create a water feature on the dusty plain three miles southeast of the little city. It became a parklike setting delighting Denverites who could visit for an “outing in the country.” The waterbody became Smith Lake and the park-like setting later became Washington Park. Water first flowed through Smith’s Ditch and filled Smith Lake in May,1867. Washington Park and the open section of City Ditch which can still be seen there today, were designated a Denver Landmark in 1977 and listed on the on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

By May, 1867, the ditch was completed to the flume which crossed Cherry Creek at what is now University Blvd. and water delivery to Denver began. The city authorized construction of smaller lateral ditches from the main ditch to make the water available to residents and businesses. The city paid for the water, initially $7,000 per year, from general taxes. According to its Superintendent, A. L. Livingston writing in 1909, at their maximum by the early 1880’s, there were over 1,100 miles of small lateral ditches located down both sides of nearly every street in the city. Their water made possible growing trees, grass lawns and vegetable gardens. Lyle Dorsett in his book, The Queen City, A History of Denver, observes, “The “city ditch” and the lawn and tree-planting spree it inspired seem insignificant by twentieth-century standards of city beautification, but for Denver in the 1860’s it was a remarkable achievement.” In 1875, the city actually bought out what was then named the Platte Water Company and assumed ownership of what had become “Smith’s Ditch”. Thereafter, it became known as the “City Ditch,” the name most recognized today. The City Ditch continues to function today in the same way it first did about 160 years ago, but most of it is now buried in a pipe.

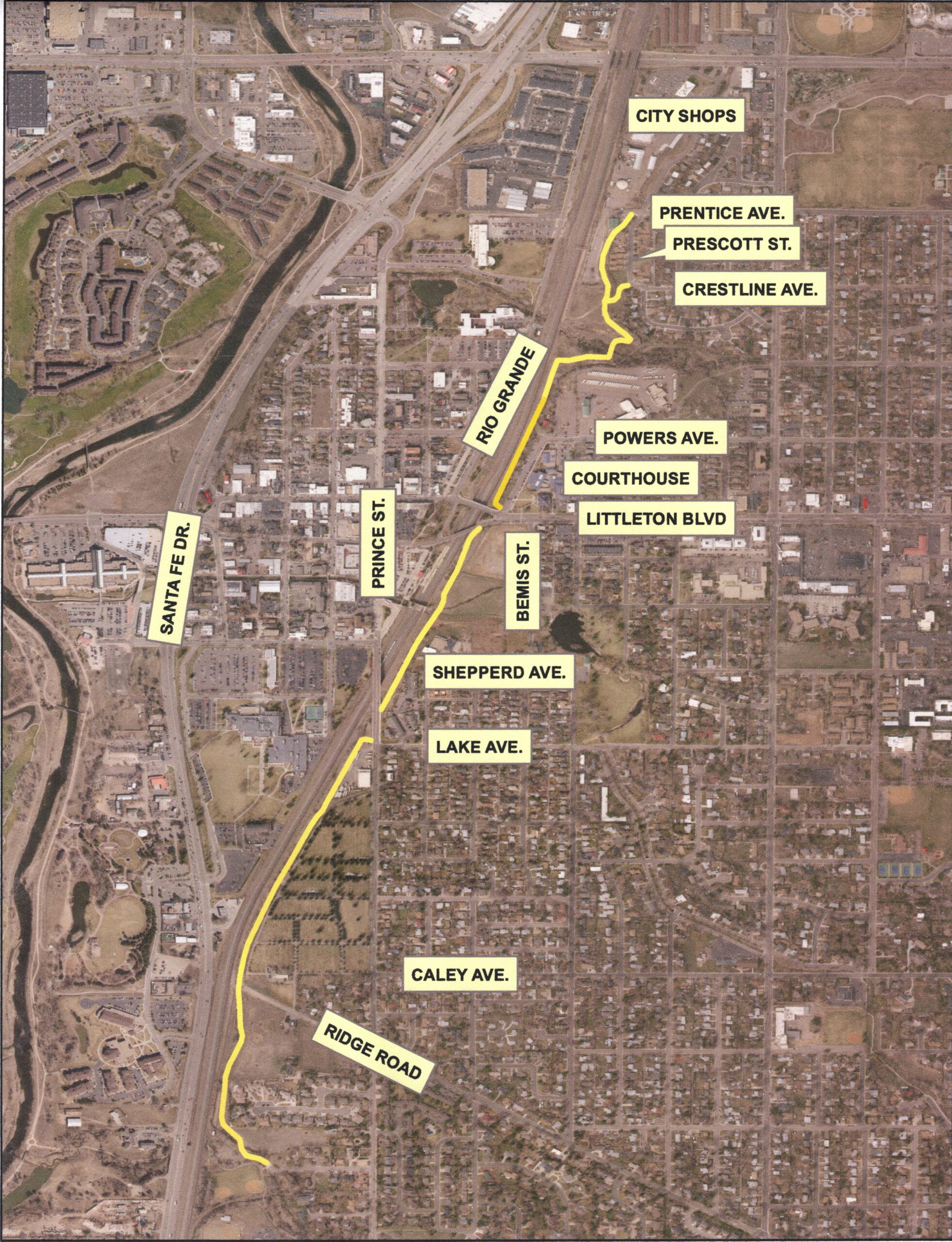

The physical property of the Ditch through Littleton has been owned by the City of Englewood for the last several decades. Platte River water is piped through the dam at Chatfield Reservoir into an open ditch south of Littleton. It provides water to irrigate the greenery at the Hudson Gardens and Events Center, the Littleton Cemetery and Geneva Park, all in the City of Littleton. The Ditch supplies water to a reservoir in southwest Englewood which is an integral component of that City’s municipal water system. Through Washington Park in Denver, the open and visible section of the ditch is managed by Denver Water. Interestingly, the water in the ditch and lakes in Washington Park and City Park does not come directly from the South Platte River but is recycled, non-potable waste water from the Metro Waste Water Reclamation District. That non-potable water, treated to a high-quality standard, is not only safe for irrigation of grass, trees and flowers in the parks but is a very wise conservation of the scarce water resources in our arid climate.

Of the original 26 miles dug between 1864 and 1867, only about 2 miles are easily

accessible and visible today. With the exception of Denver’s Washington Park, all of these visible, flowing sections are in Littleton and Englewood. Littleton’s “Community Trail” follows the Ditch right-of-way and has sections where water can be seen flowing during the irrigation season, April 1 to November 1 of each year. Water flows through the same channel that was dug across the prairie in 1864.

In Fall 2025, the City of Englewood will start construction to put most of the remaining sections of open channel of City Ditch into a buried pipe. Historic Littleton Inc provided input to the City of Englewood in an effort to preserve as much of the open channel as possible in two specific areas where the ditch is visible to the public. These areas are in Littleton north of the Courthouse in the Slaughterhouse Gulch Open Space and south of Ridgeview Park. There are two historic flumes, one in each of these areas, that have transported portions of the water in the ditch for over 80 years. When the other segments of the ditch are put in pipes, the flumes will be the most visible evidence of City Ditch. The Littleton City Council has committed to preserving the flume in the Slaughterhouse Gulch Open Space. The flume near Ridgewood Park has equal significance and can be seen directly from the Community Trail that crosses over it near the park. That flume should also be preserved.