Why Preserve Historic Buildings and Places

In preserving our heritage, we preserve our identity.

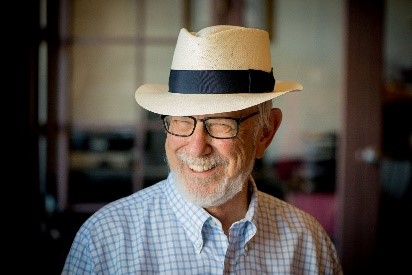

Presbyterian Church, circa 1800s.

Historic or heritage sites are the physical expression of a city’s identity. The lived-in architecture, the strategic locations, and the uses of these buildings reveal unique stories that tell how a city came to be and offer predictions of where it might be going. These features add character and beauty to a city, fostering a sense of home and community, and serving as a reminder to each of us that a city’s history belongs to all of us together. Just as these magnificent buildings have been passed down to us, we must preserve them for future generations.

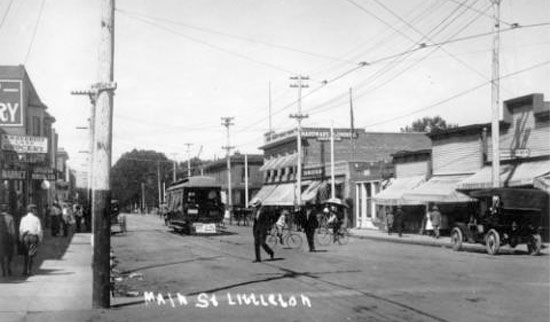

Rocky Mountain News, October 21, 1978. Photo, courtesy of the Littleton Museum Collection. May not be reproduced in any form without permission of the Littleton Museum.

Six Practical Reasons to Save Old Buildings

This section is adopted from the “National Trust for Historic Preservation/Saving Places” by Julia Rocchi and the “Old House Life” by Michele Bowers with additions by Rick Cronenberger.

What is historic and worth saving varies in the eye of the beholder, but some definition is urgent. Simply put, “historic” means “old and worth the trouble.” It applies to a building that’s part of a community’s tangible past. And though it may surprise cynics, old buildings can offer opportunities for a community’s future. The following six reasons examine both the cultural and practical values of old buildings and look at why preserving them is beneficial not only for Littleton’s’ culture but also for its local economy and future identity.

1. Old buildings have intrinsic value; they have a story

Buildings, by their very nature, are not time capsules. They often change over time through periods of use and various occupants. Architecture is a direct and substantial representation of history and place. By preserving historic structures, we can share the very spaces and environments in which the generations before us lived.

Historic buildings often reveal the human side of building construction, with each imperfection and design detail evident throughout. While museums and historic sites have their place, a building that is used and cared for is the first building block for its preservation. Not everyone expects a historic building to be used for its original purpose, but instead that it is just being used.

Above, Main Street, Littleton. Below, 2676 West main St. Bussard Motor Company.

2. Old buildings save money and materials

Buildings of a certain era, namely pre-World War II, tend to be built with higher-quality materials such as rare hardwoods (especially heart pine) and wood from old-growth forests that no longer exist.

Prewar buildings were also built by different standards. A century-old building most likely has better “bones” than its brand-new counterparts. Just the fact that they are still standing or being used is testament to their community value. Littleton’s restoration of the Arapahoe County

Courthouse is a prime example.

Preservation also contributes to sustainability–after all, the greenest building is an existing building.

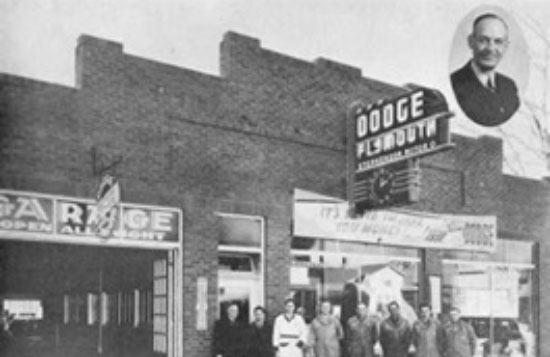

Poster image Preservation reusing America energy, 1980. National Trust for Historic Preservation.

3. New businesses prefer old buildings

Adaptive reuse of historic structures allows many businesses to use space that is authentically pleasing compared to modern-day boxes. In 1961, urban activist Jane Jacobs startled city planners with The Death and Life of Great American Cities, in which she discussed economic advantages that certain types of businesses have when located in older buildings.

Jacobs asserts that new buildings make sense for major chain stores, but other businesses—such as bookstores, ethnic restaurants, antique stores, neighborhood pubs, and especially small start-ups thrive in old buildings. That is still the case today. Look at how Downtown Littleton has thrived in the past 20 years since the Main Street Historic District was established.

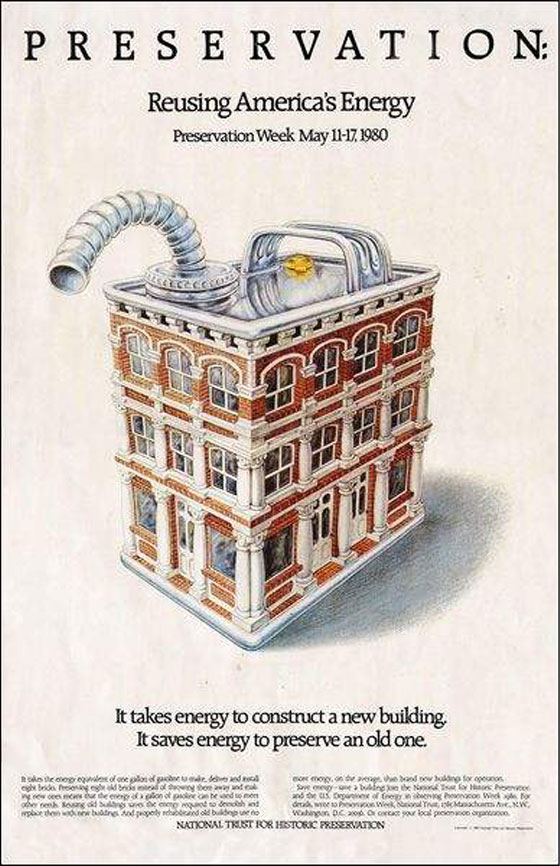

Before and after pictures of the Shelly Service Station,

on 2609 Main Street.

Examples of adaptive reuses include:

- O The ViewHouse restaurant rehabilitated the 1929 Bussard Motor Company building, and the owners saved as much of the original interior building materials as possible.

- O The Jackass Hill Brewery inhabits the Van Schaak & Company building and takes advantage of the horizontal lines and vertical windows in the Mid-Century Modern location.

- O Palenque (formerly Meryl’s) incorporates the entire original 1930s Shelly Service Station, embedded within the middle of the restaurant.

4. Old buildings have character,

attract people, and bring in new generations

Is it the warmth of the materials? The heart pine, marble, or old brick? The smell or the resonance of other people and other activities? Whatever it is, older buildings are just more interesting.

The different levels, the vestiges of other uses, the awkward corners, and the mixtures of styles offer something to talk about at the very least. America’s downtown revivals suggest that people like old buildings. Whether the feeling is patriotic, homey, warm, or reassuring, older architecture tends to fit the bill. People gravitate to archaic building materials that show aging and weathering.

Regardless of how they actually spend their lives, Americans prefer to picture themselves living around old buildings. Eyes may glaze over when preservationists talk about “historic building stock,” but what they really mean is a community’s inventory of old buildings ready to fulfill new uses.

Above, 2489 W. Main Coors Bldg., Cast Iron, Corithian Column. Below, WWW parade.

5. Old buildings are reminders of a city’s culture and complexity

By seeing historic buildings — whether related to something famous or recognizably dramatic — tourists and longtime residents can witness the aesthetic and cultural history of an area. Just as banks prefer to build stately, old-fashioned façades, even when located in commercial malls, a city needs old buildings to maintain a sense of permanency and heritage.

In Western Cities such as Littleton, whose history begins after the Industrial Revolution, our remaining buildings are like a book and each chapter tells a different story. Through architecture, the book covers the beginnings with Richard Little, the post-World War II industrial manufacturing era of Coleman Motors, and the 1950s to 1960s space age era and appropriate Mid-Century Modern Commercial architecture. The architecture all represents new frontiers, and the story continues to this day as Littleton continues to grow.

Above, Columbine Mill. Below, industry buildings on Rio Grande Street by Regal Plastics, Coleman.

6. Losing our historic buildings means losing our unique Littleton identity.

The preservation of historic buildings is a one-way street. There is no chance to renovate or to save a historic site once it is gone—it cannot be replaced. It is not just the physical building that is lost, but the sense of place, the original craftsmanship and materials, the smell and feeling, and our own individual emotional attachment to the past. Historic preservation gives identity to our city.

Historic resources are non-renewable, and we can never be certain which buildings and resources will be valued in the future unless they are surveyed and evaluated. This reality brings to light the importance of identifying, locating, and saving buildings of historic significance, because once a piece of history is destroyed, it is lost forever.

Historic resources are non-renewable, and we can never be certain which buildings and resources will be valued in the future unless they are surveyed and evaluated. This reality brings to light the importance of identifying, locating, and saving buildings of historic significance, because once a piece of history is destroyed, it is lost forever.

Above, the former REI Building, 2100 W. Littleton Blvd. Demolished in 2017.